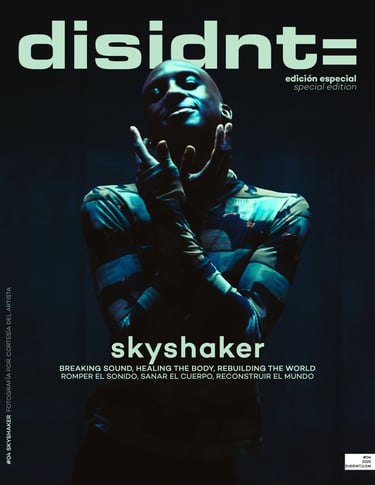

SKYSHAKER: BREAKING SOUND, HEALING THE BODY, REBUILDING THE WORLD

From iconic New York clubs to the archives of Latin American ballroom culture, from Fortnite to high-fashion runways, Skyshaker has proven to be more than just a DJ or producer. Under this alias, Sky Vemanei has built a path that defies musical genres, national borders, and conventional labels — always through a radically dissident lens.

Dante Salas

5/19/202518 min read

A composer, activist, filmmaker, ballroom historian, and educator, Sky weaves a career that is also a story of survival, reinvention, and resistance. Their sound, both visceral and atmospheric, speaks of pleasure and politics in equal measure. And even in a moment of pause brought by health challenges, Sky continues to imagine and create alternative futures.

For this special disidnt= Pride edition, we spoke with Skyshaker about their story, sonic militancy, the urgency of safe spaces, and the importance of centering Black, femme, and queer bodies on the dance floor and on stage.

INTERVIEW WITH SKY SHAKER

You’ve transformed electronic music with a visceral, powerful, and deeply emotional sound. How would you describe your sonic identity today?

It’s very contextual. I have extreme synesthesia, so as a producer it’s less based in genre and more in which sonics help match or soothe how I’m feeling. As a result my DJ sets bring that more into focus, taking on this amorphous fusion of multilingual protest music punching through industrial, deconstructed, and diasporic club sounds. It largely depends on who is in the space with me, and where we are together.

How I sound when playing in the forest or in Tresor may not be how I sound in a darkroom or a skatepark. To that end, my sound when DJing is driven more by lyrics over BPM. I love layering Black and Brown voices on top of cathartic Black and Brown music, making something rather relentless and irreverent yet ultimately hopeful.

Many of your followers have been sending love your way recently. Would you like to share anything about what you’ve been going through personally or health-wise? Has this experience impacted your art or your worldview in any way?

I tested positive for Covid in late February and simultaneously contracted a staph infection that inflamed my chronic, full-body eczema (severe dermatitis) to a dangerous level. Eczema is easily triggered by stress, so earlier problems in my personal life did not make things easier. From September last year, my passport was stolen, my visa application was denied, I lost my second job, was going through a very bad breakup, and living in a dirty apartment that I couldn’t clean by myself.

Professionally, I had lost a lot of work due to my anti-Zionist and anti-fascist stance on social media. Event promoters and record labels ghosted me and my inboxes ran dry. Meanwhile I was navigating xenophobia within the ballroom scene, medical racism, language barriers, and the unspoken social norms that come with assimilation as an immigrant. I joined several support groups, but my mental health continued to decline. In December, I acted on a suicidal ideation and narrowly survived.

The support I received was instant and steady, but was amplified even higher after I tested positive for Covid months later. The ballroom scene overcame their differences, dropped everything, and came together to create a crowdfund I am still benefiting from today. Now it’s May, and its possible I may have long Covid. Yet I have new housing, my health is recovering, and my worldview has grown to be more hopeful and optimistic as I’m now on track towards refugee status.

The last 6 months will impact my life in ways I probably won’t realize for a long time. But I’m certain that the first signs will come from the art I make next, which is both bittersweet yet exhilarating all at once.

You've been actively involved in building ballroom communities across Latin America. What does ballroom mean to you in terms of resistance, healing, and queer cultural legacy?

At its best, Ballroom is about power and reclamation of Black and Brown autonomy in my opinion. It’s a community that humanized me as a sex worker and protected my trans body as I messily figured myself out. It taught me how to speak truth to power when I was afraid. It healed me like nothing else did at the time. As a result, my work in Latin America started out as an exercise in helping nascent scenes build recognition and influence for femme queens at the industry level. Despite my language barrier, I had a lot of people volunteer to translate my thoughts, advice, and teachings for over 10 years. The legacy left is just as much theirs as it is mine in that regard.

Yet unfortunately once that influence was parlayed into investments and brands began to smell money, I began to question what kind of cultural legacy I myself was contributing to. The chasing of higher grand prizes and hierarchical titles changed the way community members treated each other. Before long, they began replicating the same structural forces they swore to fight against. It became another exercise in capitalism and classism but with nonbinary and trans flags.

As a result, my focus turned away from building recognition and visibilty and more towards building authority and protections for trans people who use Ballroom as a tool to heal into themselves. It’s easy to underestimate how much power Ballroom judges hold, and how deeply each decision impacts the mental health of those on the runway. That is why I feel developing my Streamline Scenario in Latin America is working out the way it is. It’s a more cerebral, psychological ballroom scene that takes place when Spanish is the language. That nuance in communication is ultimately what I think it’s going to take in order for this scene to truly evolve.

You’ve worked with artists from Kelela to Dashaun Wesley, and your remixes have made it into Fortnite. How do you balance sonic experimentation with a deep connection to the body and the dancefloor?

My sound has been called “deconstructed club” less for the variety of genres I work in, but more for the sounds I choose to get my points across. The majority of my music is processed recordings off of my phone. Because of my chronic illness, I’ve also used medical instruments to record how my body responds to certain stimuli.

In my Evanescence, Kelela, and Ellie Goulding remixes, I use my heartbeat as a kick and sub bass to mirror the anxiety of the original lyrics and turned my asthmatic wheezing into a reverb-laden atmosphere. So in many ways the process ends up less about experimentation and more about honesty, if that makes sense. This is especially true in my ballroom remixes, which often recontextualizes cisgender-heterosexual lyrics into something far more queer.

In past interviews, like the one we did with Fiorious, we talked about the urgent need for more women and queer people in lineups. What changes have you seen, and what still needs to happen?

For me, the issue of homogenous lineups were more of a problem before the pandemic. The excuse was always about “quality control” or something along those lines. After the world opened back up, the issue became less about identity nepotism and more about classism and access. This is especially true on the techno side of things, where you would be largely ignored or dismissed until you played HOR, Berghain, Tresor, Movement, or Boiler Room. Especially at the local level, my queer and femme friends and I have experienced this crab mentality dynamic all over the world.

This is especially true in Latin America, where machismo adds another layer of unspoken social hurdles. Its less about quality control and more about compensation and class. There are more and more queer and female artists taking the stage. The problem is they are more white and white-passing than not. They are also not being paid what they deserve nor given the time slots they deserve. Those are the issues that require more action beyond simple questioning in my opinion.

You’ve founded projects like Reiout Intergalactic and Streamline. What role does mental health play in your creative and political work?

I live with chronic depression, so the preservation of mental health is the foundation upon which everything else is built. Reiout Intergalactic uses mental health as the foundation upon which a artist’s brand is built instead of industry connections and good marketing. The Streamline scenarios restructure the Ballroom experience into something more compassionate and collaborative instead of solely competitive.

In equal measure, my remixes are often the result of what the original song did to bring me back to a place of strength. My original songs are often exercises in exploring whatever emotions feel too big to handle through conversation alone. We’ve been conditioned to not consider mental health a priority until it’s too late. I find its better to follow the quote from the Matrix, “The body cannot live without the mind”. We can’t show up for anyone else if we can’t show up for ourselves first.

You live between Mexico, New York, and Berlin. What does each city represent for you in terms of creation, belonging, and community?

New York for me is about resolve in knowing who you are and what you want. You build the resilience to push past adversity to get what you want and where you want to be, which makes it easy to see why Ballroom was born there. You learn very quickly what you are missing in order to truly take care of yourself, and how not to apologize once you figure it out.

Living in Mexico for me is about remembering who you really are when everything else is stripped away. You learn very quickly how to stand up for yourself and embrace the subtle nuances of your conversations with people.

Berlin for me is largely about organization and pivoting. Living there taught me that everything in its right place today may not be its right place tomorrow. And if someone White can easily change their mind, so can you as somebody Black or Brown. Berlin taught me the importance of boundaries and redirecting energy away from what and who doesn’t align with my values.

This also shows up in the circle of friends I have now versus when I only lived in New York. To live as a immigrant now in Mexico puts all of those lessons to the test quite often. It’s only because of the community surrounding me now that I have made it this far. My hope is that upon looking back my creative output served to be effective in passing down these lessons.

What do you dream of for the future of queer and dissident electronic scenes?

My hope is that it becomes easier to understand that dissident dreams require dissident action in order for them to come true. My hope is that it becomes easier to understand dissidence is only dangerous to those in power who make dissidence necessary in the first place. My hope is that they see how easy it is to create their own platforms that don’t rely on institutional authorities assigning value to them, especially institutions that remain silent on issues directly impact them.

Artwashing, pinkwashing, post-racialism and technofeudalism do not have to be a reality we settle for. My hope is that it becomes easier to see through the facade of neoliberalism and understand that speaking up when its unpopular and uncomfortable is exactly when its most impactful, instead of waiting for the history books to show who was on the right side of history. Boycotting, divesting, and calling for sanctions is a lot easier than it seems.

Can you tell us about something you’re working on that excites you right now?

I am sharing my Streamline project with more communities around the world, making steady progress on my live show, finalizing the first set of releases on my Xemseya label, and editing the first set of visuals re-introducing my Airiswyn and Jazgaram bodies of work. It’s especially exciting because after starting therapy in 2024, I’ve made more original music in one year than the last five. It brings into stark focus the impact of medical racism in the US and the carceral nature of certain diagnoses in favor of others.

It’s this and other sociopolitical issues in the world that are fueling my creative work now that I’m a bit older and feel the push to be more deliberate in my choices. To see and feel so many parts of me proving to be simply dormant instead of dead and squandered, it’s really exhilarating despite so much illness lately.

You started out as the lead vocalist in a nu-metal band. How did that journey evolve into club and electronic music? What part of that origin still lives in your current sound?

I grew discouraged with the way the rock scene was stagnating in my city, which was Indianapolis in 2004-2007. It was very white and purist, shooting down anyone who dared to take a risk. My band was called Kizashi Oversoul and was generally well-received in our corner of the scene, yet we were on the verge of breaking up after losing two members to drunk driving and suicide. We tried to make one last song but struggled to focus, and disbanded before we could finish. I felt especially guilty for being the vocalist and not being able to come up with anything I was proud of.

It wasn’t until I picked up my old beatmaniaIIDX and Dance Dance Revolution games from my grandparents’ house that I found myself writing again. Many songs in those games have several remixes in several genres by the same producer. Reframing my rock songs through a dance music lens became a coping mechanism that eventually became a natural starting point when making music in any capacity. Almost all of my music since then has either a rock or electronic origin story project file sitting around somewhere.

You’ve worked as a ghostwriter for major label artists. What made you start putting your name and vision at the forefront?

It happened in a series of three events. In February 2010, I turned down a record deal that essentially kept my earnings if I ever came out as queer and my sales showed my primary fan demographic was the opposite sex. Around September 2010 in Detroit, an audio engineer I was working with stole my external drive and sold the beats after I turned down sexual advances from him. Later in 2012, he was on a Grammy red carpet for projects that were clearly inspired by what we were working on together.

I was used to being uncredited on projects at the time, not only because so many would never make it to the finish line but also because I was so young and unable to afford a lawyer. I was also young and dumb and accepted other forms of compensation like flights, hotels, and invitations to celebrity events where I could network. But in February 2012, there he was on that red carpet. For the first time, I began to realize it could have and should have been me.

In that same month, the city of Indianapolis hosted the Super Bowl and Madonna did the halftime show. She invited several voguers to perform with her. By then I was in close contact with the ballroom scene in New York and was offered entry into one of the Super Bowl afterparties. Fatefully, the same engineer who stole my hard drive was there, and it was clear he was in a higher place of status among the other VIPs. I confronted him and he denied everything, but chose to brush it off by saying I had enough talent to be fine on my own. We never spoke again, yet that was all I needed to begin choosing myself and start pulling away from the major label circuit.

Your music has reached wildly different platforms — Boiler Room, MoMA PS1, Red Bull Music Academy, and even Fortnite. How does your message shift across such different contexts?

The message often stays the same, its the genre that shifts. The art and fashion world like my more deconstructed and experimental music whereas the nightlife and video game side of things naturally gravitate to my clubby and dancefloor-ready stuff. However now that hyperpop made its mark and the mainstream utilizes more organic sound design, the mission for me now is reiterating the message of why these sounds were used by marginalized artists in the first place.

These sounds were often meant to contextualize the hardships Black and Brown people overcame in order to birth these genres in the first place. So its a priority of my artistry to have lyrics, poems, speeches, and news clips putting that nuance into words. The melody and dancefloor functionality alone isnt enough.

You were part of legendary houses like LaBeija and Old Navy, and helped build the Mexican ballroom scene. What has it meant for you to serve as a bridge between communities?

It used to mean humility, gratitude, and sheer weight of responsibility up from 2014 up into the pandemic. I felt like I was given a stewardship position within the scene and had very young queer youth eagerly awaiting whatever message I was going to send next. I was reluctant at first but then chose to embrace it. I wanted to be at the forefront of Mexico’s growth in a way that was protective and proactive against the xenophobia I was all too aware of in the US and Europe.

However, trying to carry the weight of a nascent community with a language and cultural barrier is not very pragmatic and ended up causing more problems than they solved. I soon had to navigate doubts within the community itself about my true intentions for them, as someone born in the US but who had so much influence in a very vulnerable Mexican population.

To still be in this community ten years later still gives me all the feelings I felt before, yet now I feel more like a soft landing pad for leaders in the scene who need an extra push in keeping their heads up or taking difficult decisions. They may call me “Madrina” but in reality I feel more like a very proud auntie.

You co-founded Reiout Intergalactic and the ABCDLFG collective. How do you balance being an artist, activist, and educator? Where do art and social transformation meet for you?

The easiest way I’ve found is to be as honest as I can about what is really on my mind, and then turn those thoughts into something written or recorded as quickly as possible. The next most crucial part is going online or into the library and finding someone else discussing the same thoughts in their work. It’s a lot harder to feel cringe when you see other people have had the same thoughts, not only now but across all of history.

More often than not, I learn something that I want to share yet like everyone else, I don’t always like the discomfort of being outspoken. I’ve come to learn that “cringe” is just another word for courage most of the time. So my challenge lately is to build a healthier system around social media so I’m not so burned out after being online. Building a website so far has been the easiest way to balance all of these practices and focus the findings into one place.

Your references include Marilyn Manson, Ayumi Hamasaki, Sade, and Black Coffee. How do such different influences converge in your creative process?

Ayu’s versatility and originality, Sade’s clarity and timelessness, and Black Coffee’s sense of adventure and Black joy are only a few guiding lights for my creative process when I’m feeling less than I want to be. I’m less of a fan of Marilyn Manson after learning about his misogyny, yet the dissidence of his artistry and the grace of his interview responses were a strong influence in my early years.

Stronger influences would be Takanori Nishikawa, Yoko Kanno, and Missy Elliot. Versatility is often seen as indecision in capitalist spaces, yet these artists have stood the test of time because they refuse to stay the same. I turn to them when I experience adversity for creating music that doesnt neatly fit into a genre or someone else’s expectations.

You’ve created different aliases throughout your career, such as Skyshaker and Airiswyn. What does each identity allow you to explore? Why the need to reinvent?

It’s less about seeking reinvention than it is about rebirth, and revisiting parts of me that turned out to be lying dormant for one reason or another. I was an underage raver in the early 2000s, so i was into many genres at once. What may seem like a reinvention to new audiences today is really me going back to basics and embracing another part of my origin story. My “Novox 10” remix album celebrates that nuance with 10 tracks in 10 different genres. Some titles of those remixes also included the original aliases I went by before settling into the ones I use today.

Skyshaker was the first alias to crystallize in 2008 after my nu-metal days, because my music had become this heavy dance-rock hybrid that was really only being done by Skrillex, Korn, and other artists following their rise. Airiswyn came about in 2011 as a way to explore more chill sounds, release music without the major labels noticing, but also speak out against other authority figures in my lyrics. Jazgaram is the name of my own band risen from the ashes of Kizashi Oversoul. My open-format DJ sets as Skyshaker today serve as a vessel to present all of these aliases together.

You’re about to release your debut album as Airiswyn and go on your first world tour. What can we expect from this new chapter?

Unfortunately, my recent illness this year is not the only reason I have had to postpone this tour until 2026. Many events that made up the tour were postponed and cancelled themselves due to their funding being cut and artist collectives being fired as promoters for their pro-Palestine stance. However, we are part of a growing chorus of artists who are standing up to the Zionist infrastructure currently governing the touring circuit. In the meantime, I am one of many artists charting a new course for internationally travelling artists uninterested in upholding oppressive systems. All I must do is continue getting healthy.

The tour itself is incredibly exciting. After a decade of instrumentals and remixes with other vocalists, it feels surreal and exhilarating to finally share my voice in all its forms alongside my music. Airiswyn is about reclaiming that voice and using it in a way that calls for and hopefully inspires reclamation in others. It’s also the crystallization of all those years immersing myself in techno and all of the machines that make it so foundational to the Black American experience.

I never had much money growing up and don’t have much now, so the live set I’ve been able to build for this tour is a dream I’ve been working to fulfill for almost half of my life now. I’m now working my way through the visual components with a team of friends with plans on taking them along for the ride. All I need to do now is continue getting healthy.

How do you see the place of Black and queer artists in the current electronic mainstream? Is there real openness, or is it still performative?

There’s a difference between being heard, and being listened to. Afro-Latine voices are often acknowledged but rarely given the same credibility, authority, or autonomy as white-passing artists. The opinions of Black artists are being considered more often, yet their needs are taken less seriously in that same breath. Black culture is being erased with AAVE being called “Gen Z slang” and Afrobeat becoming its own industry with white DJs and producers playing in Tulum.

Discussions on racism rarely reach a level that allows for real change to occur because the education necessary to truly understand the problem has never been easily accessible in Latin America. Yet social media and the internet has changed those circumstances significantly, so there’s less of an excuse now. If the budget is there to fly someone in from out of the country, it’s a conscious decision to not include Black and Brown artists and their viewpoints from a place of strength and not as a consolation prize. This is especially true when the music being promoted is rooted in Black and indigenous music. We’re only booked if we have high social media numbers.

Performativity is the main challenge I see currently the music industry as a whole beyond any one scene. Many things we consider as career benchmarks and milestones have always been rooted in class warfare and white supremacy. Artists will say they are against the genocide in Palestine, yet continue to play Berghain, HOR, and Boiler Room events that have shown clear complicity and silence as Zionists make up the majority of their investors. It doesn’t have to be this way.

What message would you share with emerging dissident artists who dream of going to their first ball or starting a music career? What advice would you give from your experience — especially to those who still feel unsure about claiming space?

Walking a ball won’t give you magic answers towards discovering your true self, but you will get many clues. Those signs will only make sense once you act on them off the runway and in the real world. In that same breath, remember there are alternatives to finding those answers when the ballroom environment makes you feel less confident than you otherwise would be. That’s why the Streamline Scenario focuses specifically on reshaping the judging system that traditional ballroom follows. While that type of judging made more sense under capitalism, surviving under fascism requires a new lens through which to build up queer trans youth.

Claiming space as an artist can be overwhelming to those who know neither where to start nor how much would be enough to truly show up in the space properly. The answer for me is taking the messy action of allowing yourself to suck and gain quality through quantity. When your quality is not being appreciated, redirect your energy towards those who are not threatened by what you have to offer. Even then, some of these spaces can tempt you into being someone you are not. Don’t let opportunities to be in spaces that are “prestigious” or “good for the CV” cause you to betray your values.

You’ve lived in many cities and communities that surely shaped your path. Are there any people or collectives you’d like to thank for walking this journey with you? Any message you'd like to send them?

Fake Accent, Qween Beat, Chris Eclipse, Mister Wallace, AceBoombap, SVBKVLT, Unseelie, Angel-Ho, Joey LaBeija, Kia LaBeija, Casey MQ, Khalifa, Rozay LaBeija, Macy Rodman, Bottoms International, DJ Macario, Malpa, Kozovo, Underfear Records, Halcyon Veil, Gawd-X, Jay Xclusive Lanvin, Arriez, Jada Makaveli, Capital Kaos, House of LaDosha, Byrell The Great, DJ Delish, Leggoh JohVera, Ushka, DJ Straight Girl, NON Worldwide, Tienes Party, NAAFI, GHE20GOTH1K, Ravers For Palestine, Ivette Ale, Rafa Cuevas, Somnicide, Void, Pandemic Sessions, Melting Point, XMPC, Via App, The American houses of LaBeija, Old Navy, Amazon, Ferre, and the Latine houses of Colombia, Chile, Argentina, Uruguay, Canada, Denmark, Costa Rica, and Mexico. Finally, I thank my international house of Vemanei, and the Xemseyan spheres of Saved By Air.

Skyshaker’s story isn’t just about an artist making music — it’s about a body that resists, dreams, and builds through rage, joy, and radical love. In a world that often tries to erase or exploit dissident voices, Sky chooses to sound loud, sound strange, sound free.

🪐 If you’d like to support Skyshaker during their medical recovery, you can d so via the following details:

PayPal—skyshakerlife

Venmo—skyshakerstyle

Gofundme—https://gofund.me/7380870b

BBVA:

012 320 01577985886 4

012320015779858864